“SACRA NETEJA. L’ENDEMÀ” (2007) BY PAINTER JOAN COSTA AS A REVIVAL OF PERSUASIVE RHETORIC

Rafael García Mahíques

UNIVERSITAT DE VALÈNCIA

Abstract: With the arrival of modernity, the persuasive function in the production of images by those individual artists who continued to cultivate traditional visual arts withered gradually. This was due in great measure to the fact that these arts directed their attention more towards the expressive value of images than to their signifying values. On the other hand, in the 20th century, the traditional visual arts, in terms of persuasive function, have been practically replaced by the means of mass communication. The Humanist movement, as a result of a lengthy process that had culminated in the concept of compositio, defined by Leon Batista Alberti in his treatise De pictura, had learned how to orient visual art in accordance with rhetoric as a discipline that included not only verbal persuasion, but visual persuasion as well. An analysis of the work Sacra Neteja. L’endemà [Sacred Cleansing. The Day After], by the painter Joan Costa (2007), a work created for the church of the Escuelas Pías of Gandía, demonstrates the recuperation of this persuasive function by means of the combined action of image and word that configure a very concrete visual discourse by means of the use of allegory as a rhetorical device.

Key Words: Visual rhetoric, iconography, Juan Costa, Sacra Neteja [Sacred Cleansing], Gandía

Resumen: Con la llegada de la modernidad se marchitó la función persuasiva en la producción de imágenes por parte de los artistas individuales que continuaron cultivando las artes visuales tradicionales. Fue debido, sobre todo, a que dichas artes dirigieron más su atención hacia los valores expresivos de la imagen que a los valores significantes. Por otro lado, en el siglo XX, las tradicionales artes visuales han sido prácticamente relevadas, en dicha función persuasiva, por los medios de comunicación de masas. El movimiento humanista, en todo un proceso que había culminado en el concepto de compositio, definido por Leon Batista Alberti en su tratado De pictura, había sabido orientar el arte visual de acuerdo con la retórica como disciplina de la persuasión no solamente verbal, sino también visual. El análisis de la obra Sacra Neteja. L’endemà [Sacra limpieza. El día siguiente] del pintor Joan Costa (2007), creada para la iglesia de las Escuelas Pías de Gandía, demuestra la recuperación de dicha función persuasiva con base a la acción conjunta de imagen y palabra configurando un discurso visual muy concreto por medio de la alegoría como recurso retórico.

Palabras claves: Retórica visual, iconografía, Joan Costa, Sacra Neteja, Gandía.

Every image inherently embodies the purpose of persuasion. From the conceptual art developed by the earliest neighbouring civilizations that preceded our own—the Near East or Egypt—it is clear that the desire to persuade has guided all artistic creation. The autonomy of art, which emerged alongside the Greek revolution, enabled artists to create freely—without being bound by the dictates of power—and audiences to appreciate artistic poetics during the brief period known as the Age of Pericles, the classical era of Greek civilisation. Here, too, in this initial situation, the desire to communicate and persuade remained a key aspect of aesthetics. It was only with the onset of modernity—despite the revival of the concept of creative independence, elevated to a supreme aesthetic value—that the emphasis on “persuasion” began to diminish. This shift can be framed within a broader crisis in the production of images by individual artists who adhered to traditional forms of visual arts, such as painting, sculpture and engraving.

Explaining the reasons behind this crisis is complex, and that is not the goal here. Several factors contribute, with two standing out: the democratisation of visual—and audio-visual—communication, a product of the mass media revolution—a novel aspect of modernity—that has replaced the traditional “plastic arts” in their former persuasive functions. Secondly, the conventional artistic image has lost its role as a “conveyer” of knowledge, as astutely noted by Edgar Wind in his impactful series of lectures gathered in the volume Art and Anarchy[1].

Within the wealth of suggestions in this series, one of its central ideas was that 20th-century artists, having chosen to develop what had been referred to throughout the contemporary period as “pure art”[2], found themselves isolated, as their work had ceased to be, as it had been in the centuries before modernity, a means of knowledge[3]. He maintained that contemporary art occupied a marginal position, not only because science had displaced it, but also due to the centrifugal impulse of art itself: “the poet is an agent in those changes and transformations of which he sees himself as a victim”[4]. Similarly, the art of modernity was founded on its ability to surprise by dislocating our perceptual habits: “when colours, shapes, tones or words appear in bold dislocations or collisions, freed in this way from their usual immediacies and circumstances, we feel with a new intensity their quality as raw sensations”. In this way, he pointed out the proximity between “pure art” and barbarism. Moreover, innovation had become an end in itself, occurring almost incidentally to the vital functions that art was subsidiary to: art had become experimental. He also referred to the disdain for didactic art, an attitude that characterised the Romantics and continued throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. He tried to show how in other periods art participated in knowledge activities: “The great religious cycles of the past were almost all didactic: the sculptures and stained glass of French cathedrals, for example, or the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, or the tapestries of The Triumph of the Sacrament, designed by Rubens. (…) If one asks how so much science could be absorbed into art, the answer is far from difficult: great artists have been intellectually awake”[5]. From the 19th century, the reasons for the decline of didactic themes were clear: “as art folded into itself and retreated to the periphery of life where it could reign as its own lord and master, it began to lose touch with knowledge, as it lost contact with other forces that shaped our experiences. (…) As a result, [didactic art] decayed, and for all practical purposes has vanished completely: a clear sign of the divorce of knowledge and art”[6]. From that moment, artists have had to wander—self-taught—and “the isolation, which we consider essential for artistic creation, has been taken to a point where artists have to think too much because they need ideas, and those for whom thought is a primary occupation do not supply them”[7]. Wind seeks to highlight that if the artistic imagination is offered the function of instruction, it can acquire a sharp edge of refinement in responding to the instances of thought. This circumstance enabled Raphael to create The School of Athens, a sublime example of art conceived through knowledge and at its service: “as we follow the argument in Raphael’s painting, we discover visual accents, modulations and correspondences that will not be noticed by someone who does not follow the thought. The visual articulation of the painting becomes transparent and is revealed to be infinitely richer than what a ‘pure’ view that scans the figures without understanding their meaning could possibly perceive. The gaze projects differently when it is intellectually guided”[8].

This notion of “art serving knowledge” is undoubtedly the key contribution of the work I aim to introduce here: Sacra Neteja. L’endemà (2007) by painter Joan Costa [fig. 1], an artist whose career is characterised by the aspiration that his work be understood as he envisioned it, ensuring that its visual, didactic and persuasive narrative reaches the audience in line with its original discursive structure—independently of the viewer’s personal interpretation. This trait has always been a hallmark of artistic productions, which the aesthetics of modernity seem determined to overshadow[9]. To facilitate this understanding, the artist has provided a written account of his thoughts, intending that his works be completely and unmistakably comprehended in their meaning and persuasive purpose. This is crucial for the historian’s role, which, in contrast to the typical modern art critic, should start by valuing the artist’s input as a foundational source for historical analysis, wherein the historian is also free to incorporate, through hermeneutic methods, fresh perspectives that integrate the essence of artistic creation into the broader narrative of Art History.

To fulfil these purposes, I wish to offer a reading guide to properly contextualise this verbo-visual production titled by the artist himself as “Sacra neteja. L’endemà” [Sacred Cleansing. The Day After]. This guide intends to utilise the humanistic resources of rhetoric, albeit within the iconological perspective of Art History. It is important to recognise that all discourse—be it verbal, visual or a combination of both—inherently aims to be convincing and persuasive. This is because it is directed towards the dissemination of knowledge, a process traditionally governed by the principles of rhetoric from ancient times through to the onset of modernity.

The reader will understand that rhetoric, traditionally understood as a discipline of verbal language, does not inherently apply to visual language. Its foundational principles, established in antiquity by Horace, Cicero and others, were formulated within the context of verbal language analysis. However, because visual art also strives for persuasion, it is evident that it was, in some manner, influenced by rhetorical principles. This integration of rhetoric into visual art was progressively recognised within the humanist movement, beginning with Petrarch. The primary challenge in merging verbal and visual languages within the scope of rhetoric was that the nature of the former was analytical, whereas the later was synthetic. This necessitated a period of adaptation and reinterpretation within humanism. Michael Baxandall highlighted this evolutionary process, pointing to a significant development with Leon Battista Alberti, about whom he said, “when writing about painting, he no longer appears as just any humanist but as a painter—perhaps of a somewhat eccentric kind—who has access to humanistic resources”[10]. In his treatise De pictura, Alberti introduced the specialised concept of “composition”.

Compositio was not a new term in artistic vocabulary, primarily referring to the arrangement of objects in a painting. Baxandall points out that Vitruvius had used it in relation to the parts of a building (De Architectura III, i, 1), and Cicero in the context of human body parts (De officiis 1, 28). Although not unfamiliar in medieval aesthetics, Alberti redefined Compositio with a precise and novel interpretation, conceptualising it as a process with four levels. In this hierarchical structure, each element is evaluated for its contribution to the overall impact of the work, essentially a visual narrative. The process begins with the composition of planes (compositio superficiorum), which are used to form members (compositio membrorum). These members then serve to construct bodies (compositio corporum), and, finally, these bodies are used to create the coherent scene of narrative paintings (historia)[11]. Let us explore this concept in Alberti’s own terms:

“Composition is that rule of painting by which the parts of the things seen fit together in the painting. The greatest work of the painter is not a colossus, but an historia. Historia gives greater renown to the intellect than any colossus. Bodies are part of the historia, members are parts of the bodies, planes part of the members. The primary parts of painting, therefore, are the planes, as from them are derived the members and from the members the bodies and from these, the historia, which constitutes the ultimate and absolute work of a painter”[12].

In this framework, Alberti introduced an organisational model to painting, drawing inspiration from rhetorical principles. Central to this model is the understanding that the value of a painting does not reside solely in depicting a figure (colossus), no matter how virtuously rendered, but rather in its capacity to convey a story. This innovative concept, distinct from ancient or classical notions, was poised to have a lasting impact on future generations of artists and is without a doubt the most influential idea in his treatise De pictura. Just as in literary composition, where different compositional elements derive their significance from a hierarchical arrangement, this concept is mirrored in the realm of pictorial composition. In literary structure, the base unit is the word (verbum); a collection of words forms a phrase (comma); a series of phrases builds a sentence part (colon), which in turn combines to form a complete sentence or clause (periodus). This structure, and its associated terminology, originates from classical authors and features in Saint Isidore’s Etymologies, from which it appears to have transitioned into medieval rhetoric[13]. In this order, a word (verbum) is akin to a plane (superficies), a phrase (comma) to a member (membrum), a clause (colon) to a body (corpus), and a literary period or final clause (periodus) to a narrated story (historia).

Indeed, this is a method of composition for artists, requiring the construction of a narrative from the most basic formal elements. Baxandall has highlighted that this approach was applied by painters who can be categorised as adherents of Alberti: Piero della Francesca and Andrea Mantegna. Among them, Mantegna stands out for translating the visual models of Albertian compositio into the medium of engraving, effectively applying narrative compositional patterns outlined in Alberti’s treatise De pictura[14].

The Albertian model should not be misconstrued as a historiographical framework, but it undeniably provides a guide that aids art historians in approaching artistic creation more intimately. Consequently, it facilitates a deeper understanding of images—comprising works, narratives, etc.—to construct historical discourse. Although the humanistic approach of an artist like Alberti may appear overly contrived, his treatise underscores two crucial aspects often overlooked by traditional morphologist art historians. Firstly, the mutual interrelation between verbal and visual language, shaped through rhetoric. Secondly, the importance of “narrated history” as the culmination of the creative process or the overall effect achieved through a hierarchical formal creation process. This latter consideration is paramount and should always be regarded as the pinnacle of the historian’s narrative or interpretation. Traditional formalism tends to organise the narrative in reverse order: aware that history justifies the creative process, it establishes the historical narrative first and then delves into formal details, convinced that these constitute the quintessential “artistic values”, becoming the goal of the historical-artistic argument. It is noteworthy that artists themselves did not necessarily adhere to this value hierarchy. In the same treatise, De Pictura, Alberti distinguishes the technical and formal configuration of painting from its content, which he refers to as narrative or invention. This is where the creative process reaches its culmination and justification. The former—formal configuration—is dissected into three aspects: delineation through lines, composition or the union of parts and reception of light. While this demands a painter’s mastery of geometry for the former, the latter—narrative or invention, i.e., the actual “composition”—is governed by rhetoric and poetry:

“So, I assert that geometric art cannot be neglected by painters in the slightest. Following this, they can find delight in poets and rhetoricians, for these have many common embellishments with the painter. Abundant in information on many things, literates can significantly aid in constructing the narrative composition. Their principal commendation lies in invention. Indeed, invention possesses such power that, on its own, without pictorial representation, it brings pleasure”[15].

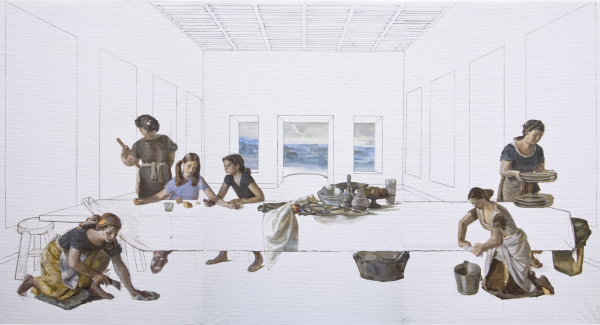

With this understanding, we can explore Sacra Neteja. L’endemà and Joan Costa, which involves two documents: the visual, seen in the pictorial work [fig. 1]—along with other preparatory visual documents [figs. 2 and 3]—and the verbal, mainly consisting of an explanatory account by the artist (seebelow), which can also be supplemented by his oral testimony. Additionally, we will consider other visual documents related to this core, particularly a subsequent version currently held by the Martínez Guerricabeitia Foundation [fig. 8].

The artist’s creation undeniably aligns with the composition process outlined by Leon Battista Alberti, which, as we have discussed, aims to invent a narrative. This process is distinct from the art historian’s task of analysing and interpreting the composition on a historical level. Our approach involves employing the interpretative process of iconology, which, more effectively than any formalistic method, integrates the artist’s composition process. This process, broadly, resonates with the lucid definition provided by this Renaissance artist in his era. Following the principles of iconology, we will first examine the “formal aspects”, metaphorically accommodating Alberti’s configuration of planes, members and bodies. Subsequently, the “approach to meaning” will delve into interpreting each narrative crafted by the artist.

Formal aspects

From a stylistic perspective, this work can be characterised as post-modern classicism. The artist has inherited a mode from the tradition that has evolved in Western art over recent centuries, infusing it with a personal touch. An essential feature is its notable closeness to nature, incorporating specific elements from relatively recent everyday life, as seen in certain aspects of furniture or clothing. This serves both an expressive and functional purpose, as the artist, breaking away from era-specific stereotypes, is conscious that doing so enhances the connection of the discursive content with the sensibilities of contemporary viewers and listeners. This aligns with a narrative discourse, although certain aspects, beyond the expressive, have been accentuated for significant purposes. For example, if the primary, natural light enters from the south through the door on the right side, the artist intentionally highlights the light from the background opening, projected through the hanging tablecloth in the foreground, onto the floor and ceiling. All of these choices clearly convey a symbolic intention, which will be explored in its proper context.

It should not be necessary to point out that, according to Alberti, the creation of “planes”, “members” and “bodies”—the formal organisation itself—represents the ideal embodiment of a process that transposes the rhetorical model of organising literary composition into painting. This holds true regardless of specific attempts to rigorously implement it, as illustrated by the mentioned engravings of Mantegna. The key insight here is the artist’s explicit desire to preserve his judgment against potential misinterpretation of his compositional intent by viewers, shielded under the guise of an expected “interpretative creativity” fostered by modern aesthetics. In essence, he has chosen the path outlined by Alberti in his concept of compositio, wherein it encompasses not only meticulous and virtuous formal organisation but also a distinct visual discourse.

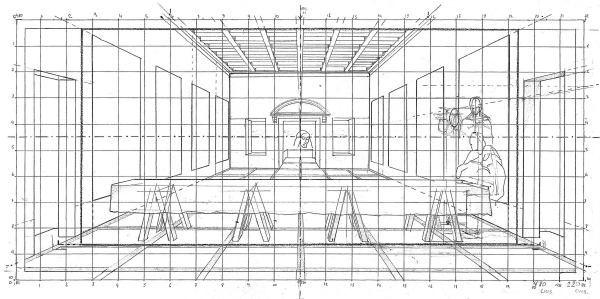

Accordingly, this section focusing on formal aspects aims to elucidate the artist’s formal organisation of his works. In the case of Sacra Neteja, the initial consideration is the configuration of the narrative stage. Clearly, the artist drew inspiration from Leonardo’s portrayal of the Last Supper, situating it in the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. The painter explains his intention to construct additional lateral spaces by opening doors, providing a broader perspective of the setting. This facilitates the positioning of characters, contributing to specific elements of the visual discourse. The sketches [figs. 2 and 3] depict his approach, extending vanishing lines from the floor, ceiling and other elements within the space.

Continuing with Sacra Neteja, the painter has also referred in his verbal discourse to certain intentional “quotations” regarding some painters. From a stylistic and expressive perspective, it is worth mentioning the following: Goya, recalling the dog from the Black Paintings at Quinta del Sordo (Madrid, Prado Museum), we see the dog being fed the leftover table scraps by the woman positioned outside the left door; Caravaggio, in aspects such as the face and bare feet of the floor cleaner, reminiscent of details from works like Judith (Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica) in the arrangement of the cleaner’s face or the Madonna di Loreto (Rome, San Agostino) in the bare feet; Van Gogh, as an artist who painted his shoes (New York, Metropolitan), as observed in the shoes near the right door; the still lifes of Zurbarán through the stacked dishes on the table; Sorolla through the effect of his Mediterranean trellises under the sun, as seen in the right opening where a woman is picking fruit from a tree; Picasso’s Guernica through the hand with the oil lamp; finally, Mondrian, in the cleaning cloth used by one of the foreground floor cleaners, with an expressive value that speaks for itself, emphasising the well-known opinion of Salvador Dalí, who derogatorily stated that Mondrian’s compositions were like used cleaning rags.

Interpretation of meaning

The central theme of this composition revolves around the cleaning of the Cenacle on the first Good Friday in history, following the Last Supper hosted by Christ and the apostles in that space. While not explicitly documented in literary sources, the artist has imagined, as something inherent in Western culture tradition, that it would involve the work of women. Though the Church as such does not yet exist, as it will be born in this very place on Pentecost, it would be, according to the artist’s document, the first cleaning of a church in the history of Christianity.

Within the depicted context, in the sense of Church, two crucial religious symbols interact, both carrying significance related to the core mystery of Redemption. The first, achieved through the visual expansion of the foreground space and the opening of doors on each side, suggests the plan of a Latin cross in line with Western basilical tradition, thus assuming the symbolic weight associated with it. The second is the symbolism of light, encompassing two distinct aspects: one of a natural and immediate nature—more a rhetorical device than a symbol—and a second aspect of a supernatural or mysterious character. The first aspect corresponds to sunlight entering through the south door on the right, an orientation the artist emphasises to imply that at that very hour, Jesus Christ is undergoing the most challenging moments of the Passion, fulfilling his Mission. This is analogised with the work of these women: “The sunlight entering the space through the right-hand door indicates that it is almost noon: Jesus is at that moment fulfilling his Mission, and the women are fulfilling theirs”. The second symbolic aspect of light is the bright light emanating from the windows at the back, contrasting with the naturalistic sunlight of midday. This light, through its physical absence, signals the supernatural presence of Christ in that space, effectively conveying the grace of the mystery of Redemption. It is noteworthy that this light comes from the east, indicating the orientation of presbyteries in early Christianity that presided over church buildings. This aligns with the first symbolism related to the Latin cross, heralding salvation under the merits of Christ’s redemptive work, the Mission of his first coming, in contrast to the western light signifying the Parousia or second coming of Christ at the end of times. Above all considerations, this symbolic content underscores the profoundly Christian nature of the visual discourse presented in this artwork. It not only justifies the presence of this painting as a worshipful piece within the church but also substantiates the array of values it presents and promotes.

In the realm of values, the artist aims to underscore the sanctification—in Christian terms—of women through the mundane task of cleaning, something seemingly inconsequential over the years: “The socially insignificant work of women cleaners has never been a source of inspiration for religious-themed paintings”. The “sacred” essence of this act, as highlighted in the artwork’s title, is pivotal. It draws a parallel, no less, between this work and the very mission that Jesus Christ is undertaking at that moment through his passion and death.

Beyond strictly Christian values, this exhibition also serves as a clear advocacy for the social dignity associated with the work carried out by cleaners: “This painting could be considered as a modest act of justice towards women who make a living by removing others’ filth”, transforming the discourse into a form of advocacy. The artist himself perceives it as a historical painting, with its very content being social advocacy: “Thanks to these women represented here, Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper transforms into the backdrop of a historical painting. From a sacred theme, it becomes a social theme, depicting a historical event that has been consistently overlooked and disregarded”.

However, the set of values extends further beyond the aforementioned social advocacy, delving into another layer of the specific discursive content of the work. This depth is also marked by the concrete intentionality, not only of the artist but also of the commissioning entity—the Piarist Fathers. While they may not have played a mentoring role in the work, as was the case in the past, they enthusiastically consent and actively engage in every aspect of the presented discourse. From an iconological perspective, the developed rhetorical framework becomes crucial for shaping a specific visual discourse, offering a precise exposition of details. In reality, we should speak of a “verbo-visual discourse”, considering that in our cultural tradition, the image has always had to complement the word for the discourse to be persuasive. This is something that the visual arts of modernity have forgotten, contributing to the crisis in image creation by artists, as noted earlier in the first part of this reflection. In line with all this, it should be emphasised that the axis of this discourse takes the form of a metaphor, a rhetorical ornatus: the cleaning of the church as a metaphor for the renewal (cleansing) of the Church (with a capital C). In a more technical sense, it involves a complete set of harmonised metaphors under this common denominator of the institutional cleansing of the Church. This would constitute an allegorical discourse if we consider allegory, as Quintilian suggested, to be “an uninterrupted series of metaphors” (Inst. Orat. VIII, 6, 44) or “a prolonged metaphor” (Inst. Orat. IX, 2, 46). The artist articulates it as follows:

“The presence of twelve women transcends historical literalness, offering, now within the realm of metaphorical meanings, a possible allegory about the Church as an institution: women work on both the right and left, some basking in the light of public recognition, while others toil in the shadows of anonymity”.

He recurs, firstly, to the contrast between men and women. There are twelve women, corresponding to the number of apostles—Jesus Christ remains symbolically present through the symbolism of light—, and in line with this, specific registers are established. The impartiality of Charity is significant: the Christian discourse transcends ideological partialities, such as political right or left, and works done in public are as valid as anonymous ones. Obviously, the women diligently scrubbing the floor in the foreground, as was done before the invention of the “mop”, provide the most persuasive reference, something that convinces through the expressive nature of the act itself, whose understanding requires no more than daily experience. But there are other significant aspects that can undoubtedly go unnoticed if the viewer only follows expressive values—which is, incidentally, characteristic of modern aesthetics, tending to leave the discourse to the viewer’s free interpretation when there are elaborations that go beyond the expressive in the original compositional discourse. It is evident that we also need the artist’s objective testimonial discourse, and not just visual expressiveness, to have a basic reference point on which to base the art historian’s discourse. Thus, we can understand that the woman feeding scraps to a dog [fig. 4] is someone who “practices charity outside the Institution itself”, i.e., individuals like the former Jesuit V. Ferrer—artist’s oral testimony—, and the woman at the opposite end picking fruit [fig. 5] is the one who, by virtue of the merits of Redemption, is capable of attaining holiness: “an elevated and redeemed Eve gathers the fruits of holiness”. Within this play of metaphors, the group at the back is very significant [fig. 6], where the ‘forewoman’, with a long command staff in hand—a clear allusion to the episcopal staff—, is shown to us with her back turned in denunciation of the refractory attitude of the current ecclesiastical hierarchy towards the concerns of younger generations, represented in the group of three girls [fig. 7] who playfully imitate the breaking of bread performed by Jesus Christ in the same place the day before, which undoubtedly should be interpreted as a prognosis of what the future access of women to the charisma of the priesthood might be. The artist is also clear in expressing all this with few words: “Some have the power to remove and appoint, turning their backs on the new generations that, as in an inconsequential game, approach the sacramental legacy”.

The painter concludes that “at this point, it ceases to be a church painting to become a painting about the Church”. In the end, everything fits within the grand metaphor of cleanliness in the sense of the necessary renewal of the old sterile clericalism. As a conclusion, the overall message of this visual discourse is condensed into the “sacred cleansing of the Church” as hope for the persistence among men of the Christian soteriological mystery.

The narrative depicted in the Sacra Neteja preserved by the Martínez Guerricabeitia Foundation [fig. 8] differs significantly and is also replicated in another canvas currently displayed in the parish church of Barx, Valencia. While the formal composition remains largely unchanged, the symbolic expansion of space created by opening doors to the right and left is absent, eliminating the spatial symbolism. Additionally, the religious and clerical elements found in the Escuelas Pías version are not present, notably the group of women removing the tapestry under the forewoman’s orders and the girls mimicking the breaking of the bread. Consequently, the Christian component is either not present or, at the very least, not essential, reducing the narrative to a focus on feminist social advocacy.

However, it is evident that the painting, in its original version in the Escuelas Pías church, is controversial and has generated both support and criticism. This controversy does not revolve around morphological or stylistic values, the compositio corporum, but rather centres on its historia. It may not be necessary to emphasise that this painting might not be considered suitable for display within a church and could be removed from its current location, for which it was originally conceived. Perhaps this has always been a concern held by the artist, and the action being performed by the two women removing the tapestry in the presence of the forewoman, who is depicted with her back turned while following her orders, might unconsciously allude to this.

The artist’s documentation as a source

A painting for the 2nd Centenary of the College of Gandía (Escolapios)

Sacra Neteja. L’endemà

Author: Joan Costa

2007

Oil on canvas, 480 x 220 cm.

I. It is the morning of Good Friday. The women are cleaning the Cenacle. Just hours have passed since Jesus and the disciples celebrated the Last Supper in the twilight of the previous evening. Now, following the Eucharist, the first cleaning of a church in the history of Christianity is underway. The sunlight entering the space through the right door indicates that it is almost noon: Jesus is presently fulfilling his Mission, while the women carry out theirs.

II. The setting mirrors Leonardo da Vinci’s painting for the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, but here it expands on both sides by extending the floor’s vanishing lines towards the base of the painting. These imagined lateral spaces encourage us to envision a more complete view of the room. Why not include side doors open to the exterior, as it does not alter Leonardo’s original conception? This way, the space adopts the form of a Latin cross, engaging the viewer in seeking the background landscape with their gaze.

III. While in Leonardo’s fresco, the protagonists are men, here they are anonymous women. The work of women cleaners, socially inconspicuous, has never been a source of inspiration for religious-themed paintings. On the contrary, a multitude of saints, queens, nuns and noble ladies fill the iconographic repertoire of the History of Painting. This painting could be considered a modest act of justice towards women who make a living by removing others’ dirt. From my childhood, I remember images of women kneeling, scrubbing the floor, with brass buckets from which they pulled dripping rags, squeezing them with their hands in characteristic gestures. In these uncomfortable positions, they carried out their work without expecting any recognition: it was their duty. And so it continued until Emilio Bellvís invented the mop back in the 1950s.

IV. Thanks to these women represented here, Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper transforms into the backdrop of a historical painting. From a sacred theme, it becomes a social theme, depicting a historical event that has been consistently overlooked and disregarded.

The presence of twelve women transcends historical literalness, offering, now within the realm of metaphorical meanings, a possible allegory about the Church as an institution: women work on both the right and left, some basking in the light of public recognition, while others toil in the shadows of anonymity. On the far right-hand side, an elevated and redeemed Eve gathers the fruits of holiness. At the opposite end, someone practices charity outside the Institution itself. Some have the power to remove and appoint, turning their backs on the new generations that, as in an inconsequential game, approach the sacramental legacy. At this point, it ceases to be a church painting to become a painting about the Church.

VI. Finally, the discerning viewer will be able to trace references to paintings from the past, starting with those of Leonardo himself. These references are encoded in the form of objects and stylistic modes that allude to famous painters, as if it were a tapestry of fragments. The original concept from which this painting started lies in this use of recycled images, previously employed. The idea is that the viewer, through their contemplation, completes the work. To facilitate this, some clues are provided to discover visual references to Caravaggio, Velázquez, Zurbarán, Goya, Van Gogh, Sorolla, Picasso’s Guernica, Mondrian, Dalí and others. Even if the author has not explicitly painted them, the viewer can identify them at their discretion, exercising their legitimate right.

Gandia, 10 March 2008.

Illustration texts

Fig. 1. Sacra Neteja. L’endemà. Joan Costa, 2007. Gandía, Escuelas Pías Church.

Fig. 2. Preparatory sketch of the composition in perspective.

Fig. 3. Final preparatory sketch. Gandía, Municipal Library.

Fig. 4. “Someone practices charity outside the Institution itself”.

Fig. 5. “An elevated and redeemed Eve gathers the fruits of holiness”.

Fig. 6. “Some have the power to remove and appoint, turning their backs on the new generations”.

Fig. 7. “(…) as in an inconsequential game, approach the sacramental legacy”.

Fig. 8. Sacra Neteja. L’endemà. Joan Costa, 2008. Universitat de València, Martínez Guerricabeitia Foundation.

[1] This volume, published in 1963, compiles a series of lectures delivered during the BBC’s The Reith Lectures in 1960. Spanish edition: Wind, E., Arte y Anarquía, Madrid, Taurus Ediciones, 1967.

[2] Thus, in our opinion, Wind perceives artistic production focused solely on the poetic-expressive aspect, demoting the objective meaning function to a secondary status. This occurs because it turns into a subjective, enigmatic and vague device, adhering solely to an individual and transient code, at times entirely forgoing this function.

[3] Lloyd-Jones, H., “Biographical Profile”, in Wind, E., The Eloquence of Symbols, Alianza, Madrid, 1993, p. 37.

[4] Wind, E., op. cit., p. 30.

[5] Wind, E., op. cit., p. 72.

[6] Wind, E., op. cit., p. 73.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Wind, E., op. cit., p. 77.

[9] As an example, consider Picasso, who once stated that he never wanted anyone to discover the process behind his creations. What was fundamentally important to him was that his expression was embodied in the images he crafted, which, in his view, spoke for themselves.

[10] Baxandall, M., Giotto and the Orators: Humanist Observers of Painting in Italy and the Discovery of Pictorial Composition, 1350-1450, Madrid, Visor, 1996, p. 176.

[11] Baxandall, M., op. cit., pp. 188-189.

[12] Alberti, L.B., De pictura, lib. II, 35. “Est autem compositio ea pingendi ratio qua partes in opus picture componuntur. Amplissimum pictoris opus non Colossus, sed historie. Maior enim est ingenii laus in historia quam in colosso. Historie partes corpora, corporis pars membrum est. Membri pars est superficies. Prime igitur operis partes superficies, quod ex his membra, ex membris corpora, ex illis historia”. Eng. tr. based on Spa. tr.: De la pintura y otros escritos sobre arte, Introduction, translation and notes by Rocío de la Villa, Madrid, Tecnos, 1999, pp. 97-98.

[13] Isid., Orig. 2, 18, 1: “Componitur autem instruiturque omnis oratio verbis, commate et colo et periodo. Comma particula est sententiae. Colon membrum. Periodos ambitus vel circuitus. Fit autem ex coniunctione verborum comma, ex commate colon, ex colo periodos”. St Isidore of Seville, Etymologies, Latin text, Spanish version and notes by J. Oroz Reta and M.A. Marcos Casquero, Madrid, BAC, 1982, p. 381: “Any sentence is made of words, and it is structed into comma, colon and periodo. Comma is a small part of the sentence. Colon is a member of the same. Periodo is the complete phrase. The comma is integrated through a combination of words; the coordination of commata makes up a colon; and, in turn, that of the cola comprises a periodo”.

[14] Baxandall delves into the analysis of Mantegna’s engraving The Lamentation over the Dead Christ, where a group of ten figures weaves the narrative of the event. These engravings resulted from the collaboration of a humanist prince, Ludovico Gonzaga, and two artists in his service: L.B. Alberti and A. Mantegna, in op. cit., pp. 193-194.

[15] Alberti, L.B., De pictura, lib. III, 53, in trans. cit., p. 114.